WHAT WENT WRONG?

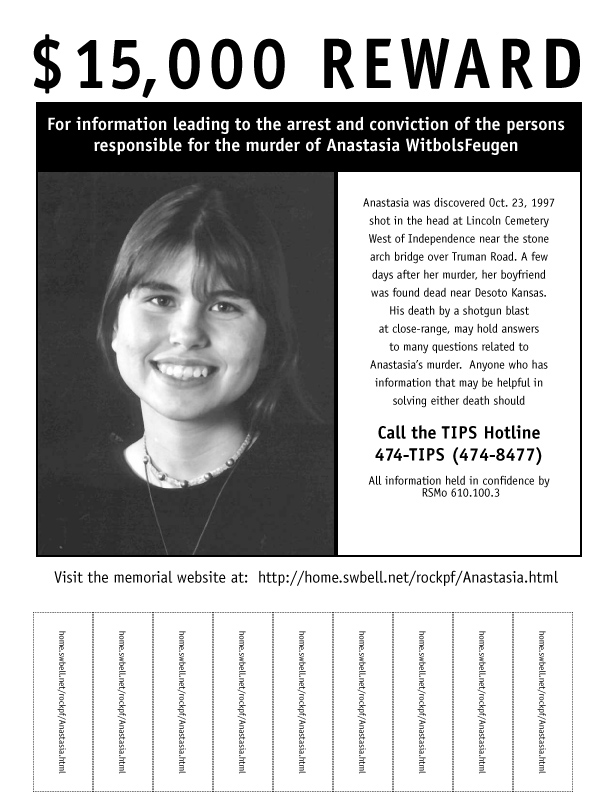

The conviction of an innocent person is almost always the result of a "perfect storm," where bad evidence mixes with investigative oversight (or prejudice), and both go unseen or disregarded by prosecutors. This is how Byron's wrongful conviction occurred — not because of a single overlooked detail, not because of one error, not because of an isolated act by an individual, but because of the slow coming together of circumstances that independently evolved after the discovery of Anastasia WitbolsFeugen's body.

The First 48 Hours | Bias | Shifting Focus

The "Confession" | The Phone Calls | Trial and Error

The First 48 Hours

Anastasia's body was found at 3:44 a.m. on October 23, 1997. Boyd Harlan, an investigator for the Jackson County Medical Examiner, arrived at Lincoln Cemetery at 5:05 a.m. He reported several factors that help determine a time of death, including a body's degree of rigor mortis (stiffening after death), livor mortis (paling, as blood settles to the body's lowermost points), and eye clarity.

The observations made by Mr. Harlan at the scene were critical to the Medical Examiner's findings since the ME only encountered Anastasia's body after it was transported to his offices. There were other facts that Mr. Harlan could have recorded if he wanted to be thorough, which would have enabled the ME to estimate Anastasia's time of death. She had apparently been killed within the previous several hours, so taking her core temperature would have narrowed the time-of-death window even more. It might have shown that Anastasia was still alive after Kelly and Byron were both home, miles away from Lincoln Cemetery, and incapable of witnessing her death.

Some resources referring to the clouding of open eyes within approximately four hours of death:

- Forensic Pathology of Trauma, by Michael Shkrum and David Ramsay

- The Handbook of Autopsy Practice, Third Edition, by Jergen Ludwig

- Spitz and Fisher's Medicolegal Investigation of Death, by Werner Spitz

As it was, the ME left the death certificate's TIME OF DEATH field blank, even though authorities in forensic pathology agree that Anastasia's "moderately formed," not fully developed rigor, plus her clear, open eyes at the scene, both indicate a death roughly two to four hours before Mr. Harlan got to Lincoln Cemetery. Despite expert consensus on these time-of-death indicators, the ME chose not to assert that Anastasia most likely died near midnight.

A bullet fragment was found, tangled in Anastasia's hair during her autopsy. It was sent to the Kansas City Regional Crime Lab, where it was weighed. A test of the lead's composition would have ruled out the many types of firearms that could not have fired the bullet, but no tests were performed at all. The absence of jacketing, wadding, or a shell — ammunition traits that would eliminate shotguns and certain rifles — was never considered. No ballistics expert was consulted during the course of the investigation.

Kelly and Byron voluntarily went to Jackson County Sheriff's Department headquarters for interviews about the events of October 22, 1997. If the officers who spoke with Byron were at all suspicious, or wanted to rule him out as a possible suspect, they could have swabbed him for gunshot residue, which can stay on the hands for days after firing a weapon. If they had, Byron's innocence (or at least his lack of involvement in Anastasia's death) would've been established at the outset.

The man who identified Anastasia from a photo shown to him on October 24, 1997, was a night mechanic at the Amoco service station about 100 feet from where she got out of Justin's car. The area canvass by JCSD Sgt. Joseph Becker was the only documented contact officers had with Mr. Rand. They never interviewed him for details about the young woman he saw walking east at dusk, away from a dark-colored car at the I-435/Truman Rd. traffic light on Anastasia's final evening. Mr. Rand's description exactly matched Kelly and Byron's accounts of Anastasia's tantrum when she left them at the light. His in-depth third-party account might have kept JCSD's homicide investigation from drifting into the realm of speculation and gossip.

Bias

Anastasia's last hours began in one cemetery and ended in another. This fact alone stood out, and any capable investigator would have worked to determine its significance. Sgt. Gary Kilgore led JCSD investigation for three and a half years. He did wonder about the cemetery connection. Unfortunately, his approach was deeply flawed. Interviews with Anastasia's family and friends left him thinking he was looking into the murder of a young woman whose associates dressed all in black, wore deathlike makeup, gathered in cemeteries, and practiced some sort of black magic or satanic rites.

Kelly and Byron's stark appearance at their October 24, 1997, interview planted a seed in Sgt. Kilgore's imagination. Byron's mention of an occult book called the Necronomicon during a discussion of Justin's tattoos only must have watered that seed. Sgt. Kilgore came to believe that Anastasia and Justin were part of a cultish group called "the Gothics." Most of his interviews with the couple's acquaintances included questions of what if anything could tell him about the Gothics' activities.

JCSD's October 31, 1997, interview with Abraham Kneisley, one of the friends who saw Justin, Kelly, and Byron after Anastasia's disappearance, marked a critical juncture. Abraham's car wasn't running, so investigators agreed to pick him up for his interview at department headquarters. Like Kelly and Byron's, a week earlier, this interview was voluntary. Still, Sgt. Ron Kellogg's questions were tinged with accusation. He revealed that one of Anastasia's school friends suggested Abraham had something to do with Anastasia's death. There's not record of what Sgt. Kellogg said on their drive to JCSD headquarters, but Abraham's prickly response during the recorded part of the interview show how frustrated he became with what was becoming a witch hunt. Sgt. Kellogg was obviously less interested in details of Abraham's October 22, 1997, timeline than in Anastasia's and Justin's alternative lifestyle interests. At the end of the interview, Sgt Kellogg tainted the atmosphere of cooperation that existed with many of Anastasia's friends when he arrested Abraham on an outstanding traffic warrant.

Some goth communities and websites:

"Goth" (or "gothic") is a difficult term to define. A broad description of goth subculture would center on its members' general standard of fashion, makeup, and music: the typical goth "look" involves black clothing and pale skin. Individual goths draw stylistic influences from any number of sources, not limited to punk, BDSM, and victorian clothing. Goth's origins can be traced to the European post-punk scene of the late 1970s and early 80 when bands like Joy Division and Siouxsie & the Banshees established the grim sound that became a hallmark of goth culture. Today's goth music encompasses many distinct genres, including darkwave, industrial, and death metal. Being goth doesn't involve any particular religious belief (or disbelief), political leaning, moral code, or conduct, it's the frequent use of romanticized death-imagery in member's art, music, writing, and fashion.

Sgt, Kilgore had Internet access. A quick online search would have turned up plenty of information about goth culture, including the alt.gothic newsgroup, many active goth chat rooms, and links to thousands of personal web pages maintained by people around the world who identified as goth. Even so, months into the investigation, JCSD remained as hopelessly ignorant on the subject as most of Sgt. Kilgore's interview subjects had been. A 1998 newspaper article quoted JCSD Cpt. Tom Philips: "My understanding of (goth cultures) is that they have groups and act out things."

Shifting Focus

Gossip spread like wildfire through the coffeehouse crowd. Speculation about the puzzle of Anastasia's death was as imaginative as it was widespread, and both Sgt. Kilgore and Robert WitbolsFeugen heard it all as they worked to find the missing pieces, Many of the rumors involved Byron: that he witnessed Anastasia's murder, that he somehow participated in her death at Justin's hand, or that he killed her himself.

Sgt. Kilgore's contact with Anastasia's coffeehouse acquaintances yielded mostly rumor and speculation:

- Interview with Steven Elliott (12-04-97)

- Interview with Alexavier Strangegroth (12-05-97)

Byron's "mad, bad, and dangerous to know" reputation developed during the year and a half he abused cocaine and wasn't totally unearned. Although Byron was no angel, not even those who disliked him most ever accused him of having violent tendencies or thoughts until Justin's suicide closed the door to many answers. Responsibility for Anastasia's death just shifted to the nearest convenient mark.

Robert hounded JCSD about their failure to solve the case. He was a man unwilling to accept the circumstances of his daughter's death. His hundreds of phone calls, emails, faxes, and letters to Sgt. Kilgore, JCSD higher-ups, and local politicians caused tension all around. Determination to see the case closed led Robert to pursue his own investigation — interviewing Anastasia's coffeehouse acquaintances, rooting through her computer files, studying her personal notebooks, analyzing her photographs, contacting her online friends, staking out locations he suspected were meaningful — nothing got him the answer he wanted. He and a friend set up a memorial website pleading for information about Anastasia's death. As time wore on, they added provocative references to the "web of silence" they thought surrounded a large conspiracy to murder Anastasia. The site was also bitterly critical of JCSD's work on the case.

Robert wasted no time reaching out to Byron by email for details about the four kids' activity after they picked up Anastasia from the DQ. Byron answered all of his questions, even after Robert turned insulting and accusatory. Byron wanted to help, but he was also in mourning — and even stalked: someone had slashed his car tires, and his father had been hospitalized with a life-threatening illness. Robert was pitiless. Once their conversation broke down, Robert's webmaster friend, Patrick Rock, stepped in to resume it, less to get answers than to point fingers.

Scattered throughout JCSD's case file is extensive documentation of Robert WitbolsFeugen and Patrick Rock's collusion to draw the investigation in Byron's direction, including:

After Byron's father died in the hospital, on Christmas Eve of 1997, Robert took Byron's unresponsiveness as a sure sign of guilt. He pushed for Sgt. Kilgore to investigate Byron more closely, refusing to accept why Byron was not a suspect. From then on, all of Robert's energy went to convincing authorities that he saw Byron's car tearing down Truman Rd. after the gunshot rang out near Lincoln Cemetery.

Robert's sudden "memory" of Byron's car got Robert multiple meetings with Sgt. Kilgore, who followed up on it even after establishing that Byron's car was in the shop for repairs that week. On August 22, 1998, Kelly sat down with Sgt. Kilgore again, as part of the re-interview process Robert instigated. She had been talking with Robert by email for weeks. During the interview, she told Sgt. Kilgore she now believed Byron knew more about Anastasia's death than he was letting on.

The "Confession"

During their relationship, Kelly was seeing a psychiatrist and taking medication for bipolar disorder. Until their breakup in January 1999, Byron had taken her to many of her appointments. Her escalating personal problems landed Kelly in a mental health facility in April of 1999. Her mother, Debra Moffett, reported this to Sgt. Kilgore, and mentioned Kelly's realization that Justin may have killed Anastasia.

Kelly was addicted to crack cocaine before the end of the year. Her parents kicked her out of the family home, after which she stayed with friends and in crack houses. She dropped in on Byron when she couldn't get food, a bed, or money anywhere else. Then Byron moved away, across the state, on September 13, 2000. Four days later, Kelly told her parents she saw Anastasia murdered. They checked her into rehab and hired a lawyer who arranged a transactional immunity deal with the Jackson County Prosecutors: Kelly wouldn't be charged with any crime if she testified. When prosecutors met with Kelly to hear her story, Sgt. Kilgore was kept out of the loop.

Without vetting Kelly's mental health, lifestyle choices, relationship history, or past dealings with JCSD — let alone verifying the established facts of the case — the Prosecutor's Office took the case out of JCSD's control. If they invited Sgt. Kilgore to weigh in on the parts of Kelly's story that were inconsistent with what he knew, there's no record of it. They also avoided discussing with her parents Kelly's mental illness, crack cocaine abuse, or overall lack of credibility. They simply ordered Sgt. Kilgore to make a record of her new story.

The first part of Kelly's resulting interview with Sgt. Kilgore gave no information about Anastasia's death that only a witness would have known. She offered no independent corroboration for her story. She couldn't say where, specifically, the alleged murder took place, nor where the gun was supposedly disposed of. She told Sgt Kilgore things (like that Justin's purchase of a gun, weeks before Anastasia's death, was "made up" to take blame off Byron) that the sergeant knew were untrue.

Listen to Kelly Moffett's various interviews with Sgt. Kilgore:

Kelly's first contact with JCSD, on 10-24-97, the morning after Anastasia's death

Kelly's first telling of her "Byron murdered Anastasia" story to Sgt. Kilgore, on 09-21-00

Sgt. Kilgore's attempt to have Kelly give him a tour of the locations in her story

Compared to Kelly's relaxed, fluid way of speaking in her earliest interview, her tone in September of 2000 should have raised a red flag. She hesitated, flip-flopped, and hedged. At several points, she laughed. In part two of her 2000 interview, which involved a drive around several locations in a sheriff's car, Kelly couldn't even identify the area of the tiny cemetery where Anastasia's body had been found. The Prosecutor's Office pressed onward, regardless.

The Phone Call

Back in 1998, when Sgt. Kilgore was following up on the impossible theories of Robert WitbolsFeugen, Byron had been reluctant to come in for another interview. He voiced his concerns to Sgt. Kilgore over the phone, saying, "I've told you everything I know," but the lawman was persistent. "No tricks," Sgt. Kilgore swore. He knew Byron's reluctance had to do with Sgt. Kellogg's treatment of Abraham Kneisley, and said as much over the phone. Byron didn't trust JCSD. Nearly a full year had gone by since the evening he watched Anastasia get out of Justin's car. He was anxious that the slightest memory lapse or misstatement would be twisted around to hurt him.

Byron got the advice of a lawyer, who listened to his full account of the facts and contacted the Jackson County Prosecutors Office. The lawyer told the prosecutor about Byron's hesitation to be interviewed about the same case again — a concern that owing to the passage of time, his words might be manipulated against him. The prosecutor offered Byron limited immunity, meaning that as long as Byron told the truth, nothing he said in the interview would be used against him. With this safeguard in place, the lawyer advised Byron to cooperate. He sent Byron to the interview at JCSD headquarters alone, and Byron cooperated fully.

Byron had an appointment to see a doctor the day after Kelly's call, for what a blog post he wrote on 06-03-01 described as "feeling dizzy and disoriented," and "alternating between sleep and vomiting":

- KU Medical Center Record (06-06-01)

Listen to Kellys' late-night 06-05-01 phone call to Byron:

The phone call to Byron that Kelly recorded on the night of June 5, 2001, echoes that earlier situation. Among the many things she complained to Byron about — Robert's harassing call, JCSD pressuring her to take a lie-detector test again, being an alcoholic and crackhead — Kelly worried that her memory was bad. Half asleep, with a high fever and a throat infection, Byron managed to tell her about the lawyer he consulted because of similar concerns two years prior.

"I told my lawyer flat-out that I didn't — I wasn't going to remember things," he said. "Told the cops that too."

His common-sense approach didn't calm her down. She got hysterical and asked to meet with him, which he agreed to, but without any urgency. He didn't offer to go over any "story" with her, and he certainly never coached her.

Prosecutors knew the June 5 phone call wasn't even close to the admission Kelly promised to try to get them, so they enlisted the Jackson County Drug Task Force to set up a controlled call. Under supervision by police, Kelly wouldn't say one word about Anastasia, her death, or anything illegal, once she got Byron on the phone again. The police presence outside his home, stationed there to arrest him the moment he admitted to murdering Anastasia, left without taking any action.

The Prosecutor's Office ultimately decided to go for an arrest, admission or no admission, On June 11, 2001, a full 265 days after Kelly told them Byron shot and killed Anastasia, they secured a warrant and dispatched the team of officers who took Byron from his home without incident.

Trial and Error

Widespread moral panic over goths lasted for several years after the Columbine shootings:

- "Oh My Goth" from The Pitch (mentions Byron)

- "Almost Half of Grant to Combat Goth Culture in Blue Springs Returned" showed the sheer ridiculousness of providing federal money to combat a non-existent problem

- "The gothic folk devils strike back!" by Richard Griffiths was published in a scholarly journal, and, though long, further debunks the goth stereotype.

- "Discrimination against Goths" by popular blog Stripy Tights and Dark Delights details how goths themselves were being attacked simply for existing

Unable to afford a private-practice lawyer, Byron was assigned a public defender named Horton Lance. Mr. Lance worked as "conflicts counsel" for five Missouri counties at once, on top of handling criminal cases in Platte City, Warrensburg, Richmond, Lexington, and Liberty — cities in every direction from his office and an hour or more away. He also tried homicide cases in Jackson County. The Investigator at his disposal simultaneously handled cases for ten to fifteen other public defenders. This wasn't unusual. An American Bar Association study recently generated scathing reports about Missouri's public defender system, suggesting the state needed to nearly double the number of lawyers on its staff before it would meet the national average. The head of the Missouri State Public Defender's Office, Michael Barrett, recently made headlines when he assigned Missouri Governor Jay Nixon to represent a criminal defendant because of the shortage of public defenders.

When Mr. Lance received the case's discovery from the Prosecutors Office, the recordings of Kelly's June 5, 7, and 8, 2001 calls to Byron weren't included. Nor were all the crime scene and autopsy photos from the Medical Examiner. In the pretrial hearing, Theresa Crayon, on half of the tag-team of prosecutors at Byron's trial, introduced the June 5 call into evidence without chain-of-custody documentation, never provided the name of the audio technician who "enhanced" the tape, and called no witness to explain the purpose, practice, or result of the alleged "enhancement." In fact, she told the court that because she didn't think providing chain of custody was required of her, she simply wasn't going to do so. Mr. Lance objected to none of this.

Byron urged Mr. Lance to subpoena Kelly's longtime psychiatrist, who could impeach Kelly's credibility as a witness. Mr. Lance stressed to Judge Charles Atwell the importance of the psychiatrist's testimony, given Kelly's reputation for making up stories. Judge Atwell only subpoenaed the psychiatrist's records on Kelly, for his own private review. He announced to the lawyers that he would look for any language in them that suggested habitual or pathological lying, but no discussion about Kelly's bipolar disorder took place. Did Judge Atwell know that lying for attention is one possible symptom of bipolar disorder, thus making her disorder a substantive issue? His knowledge of psychological disorders may not have mattered in the end, since the judge ended up only skimming the difficult-to-read handwritten notes, finding nothing in his cursory overview relating to Kelly's flair for fiction. He ordered the records sealed, and prohibited any discussion of her mental state beyond establishing that she'd seen a psychiatric counselor at some point, for some unspecified length of time.

The prosecution didn't call Sgt. Kilgore to testify, allegedly because of the bad blood that existed between him and Robert WitbolsFeugen, This meant that the only living soul with inside knowledge of the case and its complicated history — was once again kept far away from the action. Mr. Lance didn't wonder about the possible meaning of this, so he didn't bother to take a precautionary deposition from the officer, which would have gone a long way towards impeaching Kelly's testimony.

Mr. Lance was just as incurious when Robert, too, was dropped from the prosecution's list of witnesses. Only Robert could have told the jury about the late-night October 22, 1997, gunshot and all the indications around his house that Anastasia had come home in the hour-and-a-half period the WitbolsFeugen family was out.

Mr. Lance put no effort into finding friends of Dale Case, Byron's father, to testify that Dale never hunted and didn't own a gun, much less have one hanging on the wall of his home, which Kelly alleged was the murder weapon.

Mr. Lance didn't consult with or call as a witness anyone with expert knowledge of firearms or ballistics, who would have put the lie to Kelly's story about Byron using a long-barreled weapon to shoot Anastasia.

Mr. Lance failed to object to prosecutor David Fry's repeated mention of Byron's black trench coat during questioning. The words "trench coat" were commonly associated with killings after the April 21, 1999, mass shooting at Columbine High School. Hysteria in the media contributed to the myth that the Columbine shooters identified as goths — a myth so potent that some Missouri police departments adopted policies to classify goths as gang members. The city of Blue Springs, 19 miles east of downtown Kansas City, had received a well-publicized $200,000 federal grant to assess the "goth threat" there, just weeks before Byron's trial, so Mr. Fry's mentions of Byron's clothes, whether conscious or not, introduced a prejudicial element: "black trench coat" as code for "homicidal goth uniform."

Mr. Lance did object to Kelly's ploy to seem credible, but too late to prevent its damage. Judge Atwell had barred any mention of the voice-stress test Sgt. Kilgore gave Kelly in 1998 when she was still telling the truth. Court order didn't stop her from telling the jury, "I took a lie-detector test" — in a context that made it sound as if she took the test after accusing Byron. Judge Atwell denied Mr. Lance's request to clarify this for them. Instead, he only instructed the jurors to unremember Kelly's outburst.

Add Mr. Lance's fear of introducing the evidence of Anastasia and Justin's suicidal thoughts and action during the weeks and months leading up to their deaths, and is it any wonder how Byron ended up in prison despite his innocence?

Now that you understand how this travesty came about, take action to help us undo it!

Case Documents

The Jackson County Sherriff's Department file for case number 97-11829 runs to thousands of pages. For that reason, only the most materially relevant documents appear as PDFs below.

Many documents contain graphic descriptions of death and autopsy procedures, as well as potentially offensive language. Use your own discretion before reading them.

Initial Reports

- Offense Report by Dep. David Epperson (10-23-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-23-97)

- News Media Information Report (10-23-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-23-97)

- News Media Information Report (10-24-97)

- News Media Information Report (10-25-97)

Jackson County Medical Examiner

- Medical Examiner Investigator's Report (10-23-97)

- Autopsy Report by Dr. Thomas Young (10-23-97)

- Certificate of Death

Robert WitbolsFeugen, Anastasia's Father

- Interview by Sgt. Ron Kellogg (10-23-97)

- Supplementary Report by Dep. David Epperson (10-24-97)

- Supplementary Report by Dep. F.R. Scarbo (10-24-97)

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-28-97)

Diane Marshall, Anastasia's Stepmother

- Interview by Sgt. Ron Kellogg (10-23-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (11-13-97)

Francesa WitbolsFeugen, Anastasia's Sister

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-28-97)

Betsy Owens, Anastasia WitbolsFeugen's Mother

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Ron Kellogg (10-23-97)

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (11-07-97)

Dawn Wright, Dairy Queen Employee

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-24-97)

Sulaman Saulat, Dairy Queen Manager

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-24-97)

George LePage, Citizen at Mt. Washington Cemetery

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-26-97)

Don Rand, Amoco Night Mechanic

Anastasia WitbolsFeugen

- Pages from Notebook (03-18-97)

- Page from Notebook, by Anna Hunsicker (03-29-97)

- Card to Justin Bruton (09-19-97)

- Letters to Justin Bruton

- E-mail to Anna Hunsicker (10-18-97)

- Undeleted Document from Justin Bruton's Computer (10-21-97)

Justin Bruton

- ATF Firearm Transaction Record (09-27-97)

- ATF Firearm Transaction Record (10-23-97)

- Kansas Standard Offense Report by Dep. C. Farkes (10-25-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-25-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-25-97)

- Johnson County, Kansas, Sheriff's Office Report by Det. Scott Atwell (10-25-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Ron Kellogg (10-29-97)

John Bruton, Justin Bruton's Stepfather

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-24-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (01-14-98)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (02-09-98)

Abraham Kneisley, Friend of Anastasia, Justin, and Byron's

- Interview by Sgt. Ron Kellogg (10-31-97)

Tara McDowell, Friend of Anastasia, Justin, and Byron's

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (02-03-98)

Kelly Moffett

- Interview by Sgt. Kilgore (10-24-97)

- Interview by Sgt. Kilgore (11-20-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (12-10-97)

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (08-22-98)

- Statement to Jackson County Prosecutor (09-19-00)

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (09-21-00)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (09-22-00)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (09-26-00)

Debra Moffett, Kelly's Mother

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (04-10-99)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (09-21-00)

Byron Case

- Interview with Sgt. Gary Kilgore (10-24-97)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (09-10-98)

- Interview by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (07-29-99)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. Gary Kilgore (06-07-01)

- Custody Report by Sgt. Joseph Becker (06-11-01)

- Supplementary Report by Sgt. J.P. Ray (06-11-01)

If you read the documents here with interest, we recommend that you also read Byron's pending application for pardon and the accompanying personal letter he sent to Missouri Governor Jay Nixon. Then, once you have seen the evidence of Byron's innocence, we hope you will sign the petition to support his immediate release from prison.

For a thorough and impartial analysis of the case evidence and Byron's conviction, order a copy of J. Bennett Allen's book, The Skeptical Juror and the Trial of Byron Case.